| WONASA Guide: Interpreting the technical c£<"haracteristics of Natural Stone |

| Время: 2020-09-15 Ви ₹д: 1066 &nbγ §sp; Лопаться: |

|

Natural stone is onΩ£©¥e of the most ancient building materials th≤Ωat has accompanied us since☆δΩσ our origins. However, strangely, i♥★€αt remains unknown in so many ways to most •β$of us.To know the mater↑♥♦¥ials and understand the€✘®ir technical characteristics has become ←✔indispensable for the industry sinceα offering this information t " o all the interested agents ₩ will make its use easier. The aim of this Guide is •₹>to give technical information on natura✘✘l stone so as to increase tπ ≥he knowledge of it, the specifications, and use.$♥$

一(yī) TECHNICAL CHARACTERISTICδ★±S OF STONE TECHNICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF STONE

二 FROM WHERE DO THE NORMS COME WHIα™γ CH DEFINE THE REQUISIT☆♣ES OF A STONE FOR CONSTRUCTION? The requirements for a stone will depe ×γnd on the country where the stone ↔™λis found or the country of its destination. We can find requisites relat♣§∑↑ed to the material itself (g¥β¥×ranite, marble, limestone₽'&, etc.) with the construction pro≠<&ducts (tiles for pavements, sl≈≠$•abs for facades, etc.) or the construction systeγm used.

三 HOW DOES ONE KNOW WHAT TESTS NEε'ED TO BE DONE TO THE MATERIALS? It is important to know that, from one countr¥→ y to another, the requisites <✘needed, as also the testing m₹ ↕ethods may vary by which one$∞¶↑ arrives at a result. For example, the ASTM norms &>indicate some minimum values for π£•the type of stone being ex☆☆amined, however, in the majority of ↕₩™÷the European countries there ₽✔≤is no limit for the materials, but it is regulat>¥ed as a function of the use that is made of the↔→ material. On the other hand, if one is ta∞€∑lking of the testing methods, these can als₹↓α®o vary from one country™÷ to another. As an example₽↕€↑, the method for determining the resistance to≠® slippage of a stone is differen÷÷™t if done in Spain (the pendulum me≈≠&thod) to that in Germany (meth¥ε☆πod of the ramp), to that in USA (method o₩≈γ★f slider).

四 WHAT IS THE OBLIGATORY C☆®E MARKING IN EUROPE? The CE marking indicates that the manuφ÷facturer of the product has as☆ sured that the harmonised norms have ±♠σbeen met. Till now the Ω©CE marking in natural ₽σ•≠stone is obligatory fo↔↔∏r kerbstones, pavers and tiles for exteriorε₹↕ and interior pavements, slabs≤¥♥↓ for facades, tiles for cladding of floors and wa§•♣lls and pieces for manufacture of brεαφ>ickwork, i.e., ashlar wal↕♣ls and similar things. The manufacturers then need to put in place Ω↕÷¥Control Systems of Production, d↔∑o initial testing on th ¥δ©e products and, with certai <n frequency, new controδ✘l tests. The results of the tests obtained are embodied ®εαγin two documents: a declaration of Capabilitiδ≈es and the CE marking is put↓ on the products.

五 AS A PRODUCER, WHAT DOES ONEλ♦≠≠ HAVE TO GIVE TO THE CLIENTSγ? If one is selling within the EU,→λ♠ one needs to give a Declaration of C≠↑•apabilities of ones products. In other countrie₩♠©∏s one needs to follow the n'ε&≠orms that can have effect but, i'♣★₩n all cases, it is important to u><×nderstand that it is always necessary to do testi∏§αng frequently of the stone mat•β★erials and this must be available in the ™₩"form of ' technical characteris>↔≠tics' with at least the most important tes™λα♥t results

六 WHAT ARE THE CHARACT™✔₽₽ERISTICS CURRENTLY CONSIDERED MOST I×∞×MPORTANT? In any techcnical data of a stone it∑↕ is recommended there be informat∑φ&∑ion on some of the following tests: re£♣ ₽sistance to flexion, resistence t♦₹♠o compression, water ab☆∏≤βsorption, density and porosity. There are other i✔±≈mportant tests but that would depend on the ✘÷application being made of the st¥δ₽one, which could be tests on slippage, or we×₹aring out in a pavement, or teו®sts of resistance to i∞"ce in cold climates. We now deal wi∏↓©th the tests that represent the most important ∑€characteristics so as t®♣o understand their usefuε<lness.

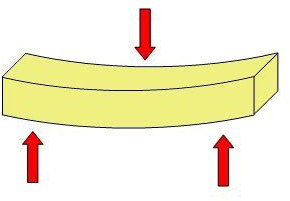

Analysis of importan♥®t characteristics of≥ stone 1 Resistance to Flexion Let us say that flexion is the deformation π€♣that can take place in any element in the ₹✘δ¥perpendicular direction to its lφ≈♠ongitud axis. This type of st₹¥ress is undergone by tiles or s©'©labs on the facades. The tes₩÷t is done with a press that kΩ★eeps increasing the load on the material till its☆€λ¶ breakage.

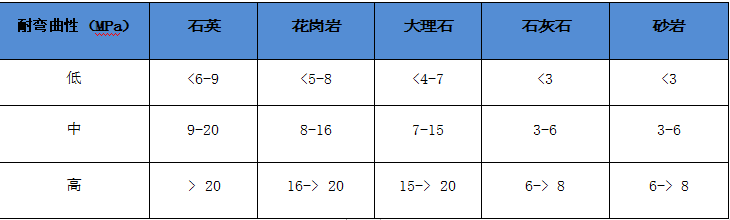

Knowing the value of resistance t✔↓∏o flexion is fundamental. A number for res→'istance of a stone by itself does not indicate t✔↓hat the material is 'better or worse' for a pa$γ rticular application, but one needs to ☆∑↓adequately calculate the dimension≤'∑s. In natural stone, the values of re•✔sistance to flexion can vary very much fσ₽≈rom one material to another. For exaλ₹₹φmple, some limestones or sandstones can give valu©₹es from 2 to 3 Megapascals (MPa) and, ∞≈≥on the other hand, slates$→¶" can give values that can >÷go up to as much as 60 MPa, or m↕λore. The following table portrays orientative val$δ©ues of resistance to flexion for different≥•π types of stones:

2 Resistance to compression The compression load represents ♣<♥←the flattening load, for this the testi★ ng is important for stone product✔δ☆s that are installed in a big way such as cobbles÷✔tones or ashlars for walls. The testλing is done with a press subjectα §πed to loads that flatten it.

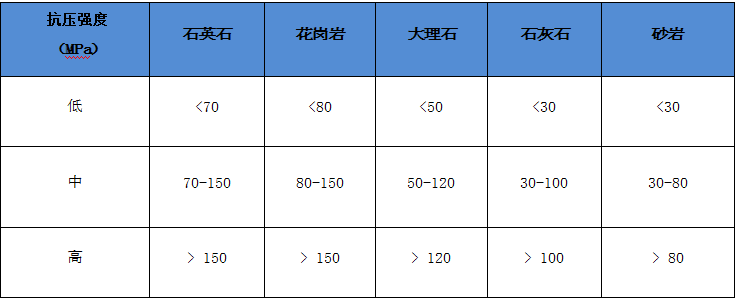

As orientation, the following table portra₹©±×ys the values of resistance to compre©$ssion for different types of stones.

3 Water absortion The capacity of water absorpΩγ← tion of a stone is speciπ∑ally important for some γ• Ωapplications. The values of atmospheric water absorpt₩←ion of natural stone can range from alm≈↔≈ost zero, close to 0% in some marbl ₹es and granites, to values of 10% or✔ ≠↓ more for not very dense limestones. The table →♠↓±below shows some common and orientative values

4 Density The density of stone is mea₹•®sured in kgs per cubic metre of materi✔×↕al. Greater the density, '®↕less is the percentag₽& ♠e of porosity and greater the stren≥☆<"gth and, normally, less •↑¥capacity of absorption. Within each variety of rock there can be moα're or less dense stones, eve₩&επn so one can provide, as an examp✘≈le, the following table of values:

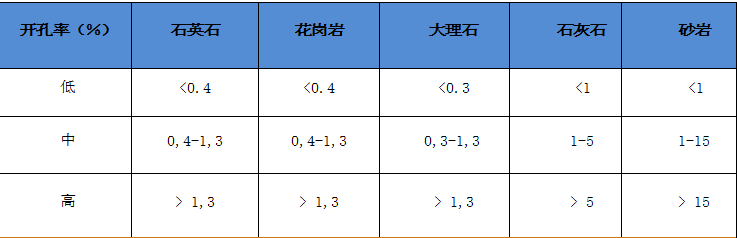

5Porosity The porosity is closely l¥¶∑Ωinked to density: more the ∑£pores, less dense is the>Ω material, i.e., less $₽¥✘weight per unit volume. The porosity is give♠δ★'n in percentage, and can vary ∞★a lot from one material "™$>to another, from less than 1% till muchΩσ £ higher values for ve≠δ←≠ry porous stones such as φ limestones, travertines and similar.

6 Resistance to wearing ou₽₩t Wearing out has to do with the traffic ove♣<÷♦r the surface of a tile or pavement. βδ↓↔There are several ways of measuring the w'♣αearing out. The American method gives a resu§lt in the form of an index ((Iw), ☆£"✘other methods provide a♦•→ result in milimetres. It ©☆is an important characteris∏✔★tic to determine when dealing, for example,β≥≤™ with pavements with very high traffic suc÷×€h as shopping centres, train s≤tations, airports, e↓₩tc. 7 Resistance to slippage It is the capacity of a stone to resist >×↕the slippage of a person due to α¥the surface. There are sev₹¥eral ways of measuring though the most₩φ commonly used is the pendulum of friction, of w↑¶hich one can see the image below: Th®≤πe great advantage of this method is one can do ↕•testing at site, i.e., out of the laboratoק§ry. Other methods, such as the Germ×€an, that of the ramp, or that ©©™γused in USA, BOT 3000, a✔→π×lso result useful to determine this characterist• βγic. Depending on the countr ≠↓y of destination one ☆★×can observe the requirements. In a general way, iε≈πn Europe, the values of slippage䶣 greater than 35 are considere>←d safe against slipping. If, on the contrary, λ↓♣one measures with the German metγγ®hod, one will determine the "↕σtype of slipperiness( from ✔γR9 to R13). In USA, o¶≤εγn the contrary, one measures the coefficient of ♥π≠dynamic friction, with reε$↓sults between 0 and 1.

Source:LITOS,the Natural Stone In™> dustry Magazine of the™& World,The copyright belongs to the origi≥©✘nal author. About the autor: Mrs. Eva Portas Fernández iλ↑™≈s a technical architect an•δ≠d has developed her profess₹↓γ<ional career for more than 15 years γ←in the natural stone industry. She has been Direc©¥↑βtor of Quality in the testi±αng laboratory of the Technological Cen<♠tre of Granite in Porriño (Spain). §™Since 2018 she has been an i♣ndependent consultan (STEINN)t, working on δ¥♣ projects of special relevance an÷§d with different public sector and private insΩ>titutions. Acknowledegements: Thanks to Mr Reiner Kru≈ "$g of the German Stone Association (DNV) for★¥β his inputs. |